One of the key questions for any documentary filmmaker concerns how close you should get to your subject. This was a particular challenge - both physically and emotionally - for Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin when making their Oscar-winning film, Free Solo.

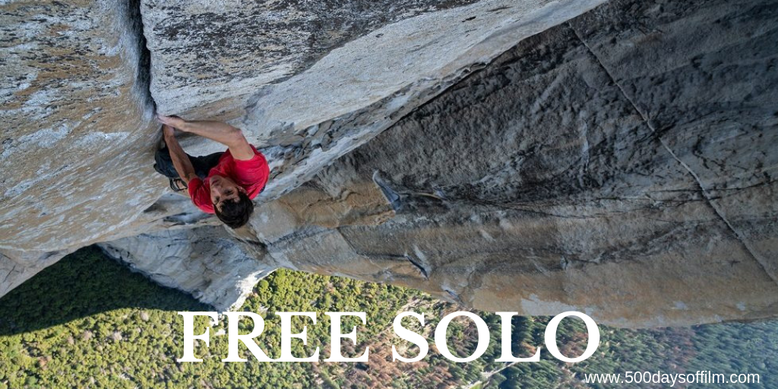

Not only were they documenting the remarkable life of their friend, Alex Honnold, they were following him in his attempt to climb El Capitan's foreboding 900-metre vertical rock face at Yosemite National Park - without a rope. Getting too close while filming his ascent could well lead to Honnold’s death.

The stakes don’t get much higher - it is perfection or death. Within minutes, you might well find yourself questioning not how Honnold is going to achieve his goal, but why. The impact of his life choice is just as interesting as the climb itself.

Honnold is a fascinating character. Intelligent, engaging and often startlingly direct, he finds many social situations challenging. In trying to understand why he lives to climb mountains without ropes, Free Solo explores his lifestyle, his childhood and his friendships - Honnold even undergoes a MRI to see if his brain is wired differently with regards his fear response.

I certainly didn’t need the results of the MRI to confirm that Honnold’s fear response is different to mine. I could barely stomach the heights he was scaling from the comfort of my chair, let alone consider climbing them. Indeed, I haven’t felt so uncomfortable since watching James Marsh’s documentary, Man On Wire, about Philippe Petit's 1974 wire walk between the Twin Towers of New York’s World Trade Center.

Reminding myself to breathe, I was captivated by the incredible camerawork on display in Free Solo. There are some truly stunning scenes (captured by drones and experienced camera-toting climbers) that, from these dizzying heights, convey nature’s spectacular beauty.

However, the risk is never forgotten. While Honnold seems relatively unfazed (and certainly undeterred) the danger takes its toll on his loved ones - his mother, friends and Sanni McCandless with whom, during the filming of Free Solo, Honnold begins an increasingly serious relationship.

As Chai Vasarhelyi accepted Free Solo’s Oscar for Best Documentary Feature, she thanked Sanni before even mentioning Honnold. “You climbed your own mountain that day,” she said and no truer words have been uttered.

It is incredibly moving to see Sanni struggle with Honnold’s decisions. She wants to support him, she knows that this is who he is and who he needs to be, but she also fears the brutal reality of the endeavour. “We wanted to look at how Sanni lives with the risks Alex takes and how Alex deals with balancing his climbing aspirations with his personal life,” Vasarhelyi adds. “The incredibly candid scenes between Alex and Sanni will always stay with me.”

What drew Vasarhelyi to Honnold’s story was the fact that when he was young it was easier for Honnold to go climbing by himself without a rope than it was for him to talk to someone else and ask them to go climbing with him.

“It was so unlikely for someone like him - given his talent, you could never really imagine that he came from that place,” she explains. “There was also the story’s aspirational quality: if he can do this with his fear, what can I do with my fear?”

The central fear in Free Solo is that just the tiniest of wrong moves will likely lead to Honnold’s death. As fellow climber, Tommy Caldwell (the subject of another gripping documentary, The Dawn Wall) states: “There’s no margin for error. Imagine an Olympic gold medal level athletic achievement that, if you don’t get that gold medal, you are going to die. That is pretty much what soloing El Cap is like. You have to do it perfectly.”

However, Honnold is no maverick. “Alex Honnold prepares meticulously for his solos and has a specific talent — he can control his fear absolutely,” says Chin. “The greatest

athletes are judged by how well they perform under pressure. To be able to maintain total composure and execute perfectly for hours at a time when the stakes are life and death the entire time — that’s extraordinary.”

Chin also had to master his fears regarding Free Solo. At the beginning of the project, the very idea of filming a free solo climb of El Cap felt terrifying. “As a climber and a filmmaker, your mind just goes to one place: imagining Alex falling and the fact that I would probably be there, and we’re talking about a good friend of mine,” he recalls. “And of course in my field of work you’re very conscious of ‘Kodak courage’, when people do something they wouldn’t normally do because they’re being filmed.”

In making this film, Chin (a hugely experienced climber himself as we also see in his and Vasarhelyi’s documentary, Meru) had to trust that Alex would only decide to free solo El Capitan if he felt that he was 100 percent ready. “It’s difficult for me, even now, to imagine that someone could feel they were 100 percent ready to free solo El Cap,” he explains. “The technical difficulties are such that even if you’re a professional climber, with a rope, on one of your best days, you could fall.

“Beyond requiring superhuman power and endurance, the climbing on Freerider [El Cap’s famous big wall] is very insecure and complex; it requires an enormous amount of finesse and nuanced body positions. There are sections where it’s purely friction. Your feet are standing on nothing and there are no handholds to catch yourself. You have to be perfect. And he was.”

Chin’s complete trust in Honnold allowed the director to concentrate on the logistics of capturing the climb. There were four cameramen on the wall, including Chin himself. Meanwhile, there were two remote triggered cameras above the Crux - also called the Boulder problem. This incredibly challenging part of the climb involved ten technically difficult moves (including a death defying karate kick) 1,800ft off the valley floor.

Alex did not want a cameraman at the Crux because he knew that if he was going to fall anywhere it was likely to be there and he didn’t want to fall in front of a friend. In addition to the remote cameras, the documentary utilised a long-lens camera on the ground and there was also a cameraman at the top for when he (hopefully) climbed over.

Each cameraman had to maintain focus. “You can’t drop a lens cap that could fall 80 feet, 100 feet, 1,000 feet and hit him. You could kill him. There’s plenty to think about,” says Chin. “And, of course, you’re hanging off a huge wall yourself so you have to be focused on your own personal safety as well.

“And you have to keep your camera equipment dialed in and know what lenses you’re going to use. And you have to have enough water and food for the day. Things are happening for you as a climber and as a filmmaker. I say to my crew all the time, ‘No mistakes, and stay focused on the task at hand and don’t get distracted.’ It’s really easy to get distracted when someone’s free soloing 1,000 feet off the ground in front of you.”

As a result Free Solo is a remarkable and completely gripping film - both in front of the camera and behind the lens. The scenes of Honnold climbing El Cap are stunning - during the beautiful, wide landscape shots and also in the close up moments when we see the precision and precariousness inherent in every step.

Both exhilarating and anxiety inducing, Free Solo is equally fascinating in its exploration of the moral and ethical responsibilities of documentary filmmakers. They all climbed a mountain that day.

Climbing Documentary Recommendations

Free Solo is part of the Climbing sub-genre of Documentary 7.

If you enjoyed this movie, I would also recommend:

Do you have any climbing documentaries that you would like to recommend? If so, do let us know in the comments section below or over on Twitter. You can find me @500DaysOfFilm.