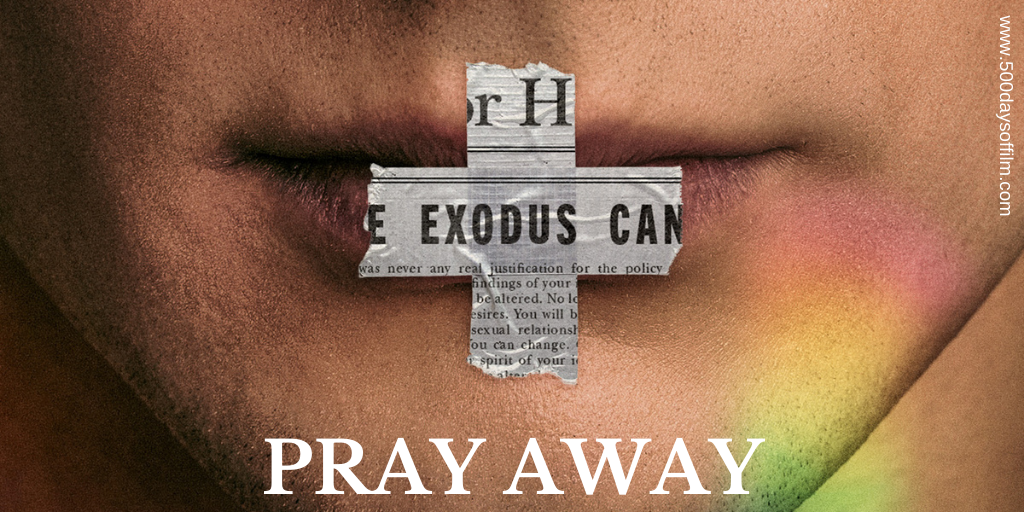

I had, for some reason, begun to think that gay conversion “therapy” was a thing of the past - an ill concieved and damaging chapter in LGBTQ history. After all, most medical and mental health organisations have long denounced this practice as being incredibly harmful. However, as Kristine Stolakis’s powerful documentary, Pray Away, shows, as long as homophobia remains in the world, conversion therapy - in one form or another - will continue to exist.

Proving this point right from the start, the film begins by introducing us to ex-trans woman, Jeffrey McCall. McCall truly believes that, having “left everything to follow Jesus Christ”, he has been set free from the “bondage” of his sin. While Pray Away does not seek to judge McCall, his presence is proof that the “ex-gay” movement is far from a thing of the past.

As a result, it feels vitally important to understand how this movement began and how it rose to power in America. And who better to tell that story than some of the original conversion therapy leaders themselves? Stolakis’s film features commentary from the co-founders and senior figures of Exodus International, the largest and most controversial conversion therapy organisation in the world.

We hear the stories of Micheal Bussee, co-founder of Exodus, Yvette Cantu Schneider, former director of Women's Ministries at Exodus, and Randy Thomas, former Exodus executive vice president. In lesser hands, Pray Away could easily have portrayed these people as villains. There certainly is more than enough evidence - in the form of shocking archive footage - to show the damaging role they all played in promoting gay conversion therapy.

However, Stolakis is not interested in pointing the finger of blame. She does not sensationalise their past - no matter how controversial. Her approach is one of intimacy, respect and sensitivity (Stolakis’s style reminded me of Sarah Polley’s superb doc, Stories We Tell). There is far more to be gained from listening to their stories with an open heart and mind.

As a result, we get an incredibly powerful look inside the minds of those who truly believed that the only way to be happy and accepted - by their family, by their religion and by society - was to deny their true selves and their communities. “I was the most famous ex-gay person in the world,” claims John Paulk, a former board president of Exodus. Speaking directly into Stolakis’s camera, he admits, with shame and guilt, that he lied.

Paulk is not alone. As Exodus offered a way to pray the gay away, its leaders harboured a secret - their same sex attraction never actually went away. After years as Christian superstars in the religious right, many of these men and women came out as LGBTQ, disavowing the very movement they helped start.

Julie Rogers came out to her mother when she was 16 years old. In Pray Away she recalls that her mother became “frantic” at the thought of having a “potentially gay kid”. As a result, she took Rogers to see a man called Ricky Chelette. Chelette was a leader of Living Hope, an Exodus affiliate ministry. “I really didn’t want to meet him,” Rogers explains in the film. “It just felt awkward and weird and unlikely to work.”

We know that it didn’t work because Pray Away introduces us to Julie’s finance, Amanda Hite. In moving scenes full of love and light, we watch as the couple prepares for their wedding. It is impossible to understand how anyone could look at their relationship and condemn it as being sinful and wrong.

However, Rogers spent years under the direction of Chelette being told that she was a “bad” person for being gay. Unable to suppress her true self, she began to spiral into shame and self harm. It is heartbreaking to hear Rogers’s story - even as we know it has a happy outcome. A survivor of conversion therapy and still very much invested in her religion, she now uses her experiences to help others.

It is fascinating to hear how so many of the ex-gay movement’s leaders came to understand the damaging nature of their words and actions. At the end of Pray Away, Randy Thomas breaks down in tears. “I can’t look back and say ‘this deserves forgiveness’ or ‘I deserve forgiveness’ because I don’t,” he says. “What I did was wrong. It was so wrong”. Looking back, he cannot understand why or how he could betray his own community in such a way.

Yvette Cantu Schneider also cannot stand that she was once a part of the ex-gay movement. “All it does is damage,” she explains. While Pray Away does not condone or encourage the forgiveness of their actions, Stolakis recognises their humanity, their bravery and the power of their testimony.

“When you finally realise how much harm you have done, it’s a crushing realisation,” says Micheal Bussee. “It’s a devastating feeling. But apology only goes so far. You really can’t go back and give people back those years that they wasted trying to be ex-gay. All you can do is, from this point forward, speak out against it - and speak out strongly against it.”